New scientific and technological discoveries transformed agriculture in the United States during the twentieth century: increased mechanization, hybrid crops and industrial fertilizers, to name just a few. Alongside these came a shift from small independently owned farms to large agri-businesses. More and more, farmers depended on other branches of the agricultural industry to supply them with the materials they needed to farm. And all of this took place during a series of dramatic swings in the global economy.

In the 1910s and 1920s, most of these changes lay beyond the horizon. But this did not mean that agriculture stood still during those decades. Urbanization and industrialization were transforming American society, including American farms. Agricultural reformers wanted to bring scientific rationalism, efficiency and expert knowledge to bear on the challenges facing American farmers. Agricultural scientists were keen to communicate new methods and discoveries. Farmers, too, wanted to know what agricultural science could do for them. Agricultural schools and research stations already had extension services through which the latest agricultural research was communicated to farmers, but something more was needed.

In the 1910s, a network of Farm Bureaus was created to address this problem. Farm Bureaus were local organizations that functioned as a point of contact between farmers, agricultural research institutions and government agencies. They provided farmers with a forum to organize among themselves to battle common problems like agricultural pests and livestock diseases, and they had a political role as lobbying organizations. Within a decade, local Farm Bureaus had state-level organizations and soon a national one as well, the American Farm Bureau Federation. The connection to science and scientific expertise that the Farm Bureaus offered to farmers was crucial. Access to scientific farming techniques gave Farm Bureau members a sense of authority and expertise; farmers hoped that the rational application of the latest research would help them make their way into larger national and international markets and grapple with changes brought by industrialization. Extension services and local Farm Bureaus, in other words, are part of the history of agriculture in the United States, but they are also a part of the history of science and technology. We don’t aways think of local agricultural organizations when we think about the history of science, but we should.

The development of Farm Bureaus in the United States overlapped with the First World War (1914-1918). During the First World War, demand for American farm commodities skyrocketed. The conflict devastated Europe, and European farmers could not produce enough to feed people. In response, the U.S. government encouraged American farmers to produce more, offering loans to finance new equipment and the cultivation of additional acreage. To make the most of this opportunity, farmers needed the information that agricultural schools and research centers could provide. Local Farm Bureaus and agricultural extension services helped farmers navigate this new situation.

New York State was in the vanguard of the Farm Bureau movement — one of the key figures in the development of the Farm Bureau idea was John Barron, a farmer educated at Cornell University who worked as an extension agent in upstate New York. With its outstanding agricultural school, Cornell played a key role, alongside business groups, rail roads, local chambers of commerce and businesses like Sears Roebuck, in organizing Farm Bureaus in New York State in the 1910s. Federal funding arrived in 1914, with the passage of the Smith-Lever Act, which established a national cooperative extension service to provide access to agricultural information.

How did these global and national changes play out on Long Island? In the 1910s, Suffolk County farmers decided to work together to market a particular variety of seed corn, Luce’s Favorite. Who was Luce, and why was this corn Luce’s favorite? We don’t know exactly. The family name Luce appears in Suffolk county, but it’s not clear which member of the family the name refers to, or when the variety was named. The story of this particular variety and the plan to market it offers a local, personal version of a much bigger narrative, connecting the work of farmers, the Farm Bureau, agricultural science, the study of genetics, and the social and economic history of Long Island.

The story begins in October of 1917, towards the end of the First World War. New York agricultural extension agent John Barron published an article in the monthly journal of the Suffolk County Farm Bureau, “The Production of Luce’s Favorite Corn for Seed.” Barron reported that Luce’s favorite was a standout silage corn. (Silage is food for ruminants, typically livestock like cattle and sheep, made from cereal crops that have been stored and allowed to ferment.) He went on to describe how the local Farm Bureau was recommending it, and that “Luce’s Favorite has also been pushed in a small way by some seedsmen and growers.” Luce’s Favorite appears to have been a Long Island original. According to Barron, “it has been well known that Luce’s Favorite has been largely developed in Suffolk County,” and that Suffolk County was the source of “the best stock.” Opportunity was knocking, and a new constellation of organizations and institutions suggested a way to take advantage of it: when Cornell “University came into touch with the newly established Suffolk County Farm Bureau regarding demonstration work in the county, it appeared that something should be done to foster the production of more and better Luce’s Favorite corn for seed.” That is, Suffolk County farmers would grow Luce’s Favorite and sell the grain as seed to those who wanted to grow silage corn. If the effort was organized and carried out correctly, Suffolk farmers could earn a considerable amount of money with Luce’s Favorite. Barron presented it as a chance for local farmers to cooperate with one another to get ahead.

But in order to be marketed, the variety had to be uniform. In 1917, corn was field pollinated, which meant that genes from various fields could mix, and after each harvest, farmers individually chose which ears to save as seed and plant the following year if they wanted to continue growing the variety. As a result, a given type of corn could vary from place to place. The quality of the soil also played a role. This was the case for Luce’s Favorite. Barron noted the the variety was “evidently a cross between a dent type and a flint type” and “assumes many different characters…tend[ing] to flintiness on poor soils,” while “under better conditions it develops a marked tendency toward dent.” (The kernels of flint corn have a hard outer layer, while dent is softer and starchier and each kernel develops a distinctive dent, hence the name.) When Barron was writing in late 1917, there was “not a well defined and well-developed type” for Luce’s Favorite, which would need to change if farmers were going to market the variety.

How did farmers and agricultural experts go about determining and defining a variety like Luce’s Favorite? Unlike today, there was no genome sequencing — the discovery of DNA still lay over thirty years in the future.

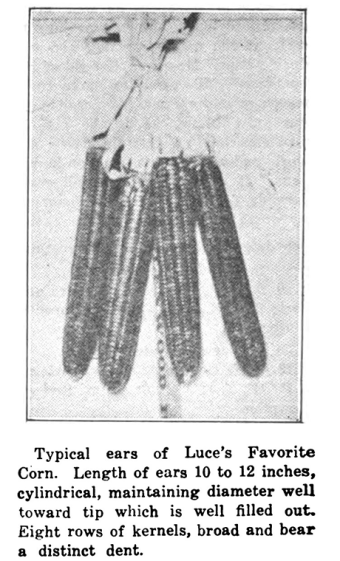

They worked based on phenotype, on how the corn looked. The expertise of farmers was central this process. Through “visiting many fields and conferring with many farmers who were familiar with the variety, a type was found” which could be used as a reference for those interested in growing or marketing this corn: “length, at least 10 or 12 inches with a greater length if undue coarseness does not develop; eight rows of kernels, which are broad, well-developed and bear a distinct dent, though not so markedly as is the case with dent corns; ears cylindrical without undue coarseness at the butt, and maintaining their diameter toward the tip, which is well filled out.” This description was accompanied by a photograph (see above). Corn experts familiar with the variety would know it when they saw it.

To market the variety, a lot of work was required to ensure quality and consistency. It was necessary “to inspect as many fields of Luce’s Favorite as can be found to determine where true seed of the variety is and who holds it,” to meet “to discuss type and methods of seed selection; to get some growers to select good stock for their own use; to get some growers to give careful attention to seed preservation and to compare results with seed selected from the crib; to make germination tests of the seed stock of such growers as wish to offer their stock for sale, and to publish a list of growers who have good stock which germinates well and call it to the attention of the up-state farm bureau managers.” Growers, seed sellers and the Farm Bureau were all involved and the process of defining and marketing this variety of corn. None of them ‘owned’ Luce’s Favorite the way seed companies and biotechnology startups would develop, patent and legally own specific varieties decades later. Field-pollinated varieties of corn like Luce’s Favorite belonged to everyone and no one, which could lead to problems. Barron mentioned in his article that seed corn was being sold as Luce’s Favorite which “was nothing more than common yellow flint.” This made buyers “suspicious not only of Luce’s Favorite corn but of Long Island corn in general.”

How could producers ensure quality and consistency? The solution already existed, and it had emerged from the growth and establishment of agricultural science at universities and research stations. Many of these research institutions had crop breeding programs and provided farmers with the seeds for the varieties they developed. To make the process of getting the seeds to the growers more efficient, land-grant universities and state agricultural experiment stations “encouraged the establishment of crop improvement associations and seed certification programs. These were established in most states between 1900 and 1930,” as historian Jack Ralph Kloppenburg explains. Certified seed had to be tested to make sure it conformed to the standards set for the variety, and the law required sellers to sell it under the original name of the variety. Suffolk farmers formed the Suffolk County Seed Corn Association in December of 1917 after a meeting in the town of Mattituck. The association acted as the storefront for its members. Farmers joined, had their corn inspected and certified by agents from the Suffolk County Farm Bureau and the State College of Agriculture at Cornell, and the corn was then sold through the association. The bags bore the trademark of the association and had a tag to show the product was certified. Farmers received a good price, and buyers could be sure that they were getting a quality product that would meet expectations. It’s worth noting that this seed corn association was not the only such organization. The local Farm Bureau news noted that this was just “the latest organization to be formed to advance the interest of farmers in the county.” The first decades of the twentieth century saw many such local agricultural cooperatives all over the United States, often associated with local Farm Bureaus.

Did the plan work? The short-term answer was yes. In 1918 the Farm Bureau newsletter reported a rosy outlook for the plan. The seed corn association had shipped Luce’s Favorite seed corn to about 5000 farmers in New York State, and “many of them pooled their orders through county seed committees, Farm Bureaus and the Dairymen’s League.” According to the Farm Bureau, not only were Suffolk County farmers making money, but farmers upstate were saving money as well, since they were getting the seed corn more cheaply from the cooperative association than they would have from seed dealers. The cooperative association also purchased machinery for shelling and grading corn and set up a plant in Mattituck which went into operation in 1919. The association made efforts in 1919 to further standardize the variety by requiring farmers who planned to sell Luce’s Favorite through the association to buy their seed stock there. The reason was that the variety was a mixture of flint and dent, and as a result “will vary from nearly a pure flint to a pronounced dent in type and from a deep orange color to a pale yellow under the selection of different growers and it is not practical to market corn with such a wide variation as high grade seed corn. Therefore, it is necessary for the Association to breed its seed to a uniform type. The stock seed will be specially selected from cribs of the right type and from high yielding stock” This decision was intended to create a more uniform product — but it also gave the association a little bit more power over how its members produced Luce’s Favorite. Given that the association was made up of precisely those growers who produced the product, however, the shift in power was not enormous.

The fame of this Suffolk County seed corn association spread beyond Long Island itself. As noted earlier, the first decades of the twentieth century saw an explosion of self-organization among farmers to meet the challenges of the new century. This development was not lost on scholars and commentators interested in agriculture, labor relations, and/or the economic circumstances of rural life. Late in 1919, at a conference in Wisconsin held by the American Association for Agricultural Legislation, a professor of rural economy at Cornell described the Suffolk County seed organization as an important example of collective bargaining in agriculture and described how the association worked. A paper about collective bargaining in agriculture may seem only loosely connected to the history of science, but as we’ll see, the relationship between farmers and the rest of the agricultural industry — what they produced themselves, and what they had to buy, from whom, and for how much — is key to understanding the history of agricultural science and agricultural biotechnology.

The Suffolk County Seed Corn Association appears to have peaked in the late 1910s and early 1920s. By the mid-1920s, growers were still selling Luce’s Favorite, but a notice in the Suffolk County Farm Bureau News in December of 1924 suggests that the Association was no longer connecting growers and buyers. The brief advertisement told readers that “There is a very limited supply of Luce’s Favorite Seed Corn this year and because up-State farmers are demanding it,” Suffolk County growers who had it could make some money. “The County Agent can help these growers sell their supply at a good figure if they will get in touch with him.” It was the county agent, in other words, who would help farmers connect to buyers. The Seed Corn Association was not mentioned. Luce’s Favorite was still being offered for sale in the later 1920s — the ad that the Mattituck Seed Store ran in every issue of the Farm Bureau News noted that this store was the “headquarters” for Luce’s Favorite. By the 1930s, the variety seemed to have disappeared.

What had happened? Two things had probably combined to put paid to the Suffolk County Seed Corn Association and Luce’s Favorite. The first was a political and economic development. Demand for American farm products remained high in the first few years after the end of WWI in 1918, but by the early 1920s, Europe was recovering from the conflict and farmers there could produce more. Demand for American wheat and corn fell — but American farmers continued to produce significant surpluses. Many had debts to pay, which was an incentive to produce more, and they had grown used to farming larger areas and making use of equipment that made the process easier. The result was continued surpluses and low prices, which was good for consumers, but not for producers. The rest of the American economy boomed during these years, but it was a difficult time for anyone trying to make a living growing wheat or corn. It is likely that that Suffolk County farmers’ enterprise to market and sell seed corn fell victim to this general agricultural depression in the 1920s.

The second important change was a scientific one: the discovery of hybrid corn. Although Cold Spring Harbor geneticist George Shull had discovered the basic principle behind hybrid corn decades earlier, commercial hybrid seed was generally not available to farmers until the early 1930s. The economy was likely behind the demise of the Suffolk County Seed Corn Association, but hybrid corn was the culprit in the case of the Association’s product, Luce’s Favorite. In short, it looks as though Luce’s Favorite, like many other older field-pollinated varieties, was simply replaced by hybrid corn. One Long Island discovery had eclipsed another.