Hybrid corn revolutionized American agriculture. By the 1940s and 1950s, farmers were getting yields that would have astonished their grandparents. And it was no surprise that a change on this scale transformed daily life for farmers, as well as their relationship to other parts of the agricultural industry. How did this biotechnological change play out on Long Island?

The transition from open-pollinated to hybrid corn on Long Island began during the Great Depression in the 1930s and was mostly complete by the late 1940s, after World War II. During the 1950s and 1960s, farmers began to face some of the challenges that arose from a more industrialized style of agriculture. Plant diseases spread more quickly and were harder to eradicate because crops had become more uniform, for example. Farmers also needed to use significant amounts of artificial fertilizer to get the most out of the new hybrid varieties. The relationship between scientists and farmers remained important, although the balance of power between farmers on the one hand and agricultural scientists and agribusinesses on the other shifted during these decades.

Readers of the Suffolk County Farm Bureau’s monthly newsletter would have started reading about hybrid corn around 1932, over twenty years after Cold Spring Harbor researcher George Shull had first come up with the idea. It’s not surprising that it took a few decades for a scientific discovery to be translated into a practical application — even though Shull had worked out and published a method for breeding hybrid corn by 1909, there were still hurdles to overcome. According to the Farm Bureau, canners had had access to hybrid sweet corn “at a high price” since the late 1920s, but it was only in the early 1930s that other corn growers got regular access to hybrid seed.

What convinced farmers to switch to hybrid corn? The two biggest factors were increased yield and disease resistance. Agricultural prices had dropped within a few years of the end of the First World War and remained low through the 1920s. The beginning of the Great Depression in 1929 did not improve things for farmers. Sellers of hybrid seed emphasized the increased yields possible through hybrid plants; plants that produced more grain per acre made up for the low price farmers received per volume of grain. Disease-resistant hybrids also increased yields and thus profit for farmers — hybrids resistant to bacterial wilt, which was a big problem on Long Island, were a major factor in convincing farmers to grow hybrid corn.

In 1933, the Suffolk County Farm Bureau brought hybrid corn to farmers’ attention in an article about the best way to combat bacterial wilt, a common corn disease that was a significant problem for corn farms on Long Island and elsewhere. The best choice, the Farm Bureau said, was to grow resistant varieties, and “the new hybrid strains of sweet corn offer the best possibilities.” There were many that are fairly resistant to wilt, although some were more resistant than others. Because the cost of the seed was a factor, the article explained that the costliest hybrids were the “F1 hybrids,” with “top-crossed hybrids” being slightly cheaper. The article emphasized that “anyone who has not tried any of the new hybrid varieties should get a little for trial purposes.” Farmers wanting more information would have had to wait a few months until the April issue of the Farm Bureau’s newsletter, in which an article entitled “Hybrid Sweet Corns” explained the distinction between F1, double-cross and top-crossed hybrids. The last of these was a cross between an inbred line and an ordinary field-pollinated variety of corn. There was quite a bit of this type of seed on the market in 1933, probably because of the cost of hybrid seed. It was “intermediate in merit between F1 hybrids and strains selected in the usual way.” Finally, the author warned of some potential pitfalls with the new hybrids. The hybridization process itself wasn’t the problem. Rather, it was unscrupulous sellers: farmers should “keep a weather eye open for offerings that may not measure up to proper standards, particularly as this class of seed becomes more popular.” They should “compare results carefully with those from ordinary strains,” purchase their seed from reputable dealers, “compare results with other users, and draw your own conclusions.” By 1935 or so, hybrid corn was rapidly gaining ground in comparison to traditional varieties.

Hybrid corn made farmers more dependent on seed companies. With the traditional field-pollinated varieties of corn, farmers saved some ears from each harvest to plant the following year. This strategy didn’t work with hybrid corn. If you planted the seeds from a hybrid crop the following year, this second crop would not have the hybrid vigor of the first and would be much more unpredictable in its characteristics. As a result, farmers had to buy hybrid seed each year. This in combination with the higher cost of hybrid seed in its early years made some farmers cautious about growing hybrid corn. A vegetable specialist from Cornell noted in 1935 that hybrid corn created a “striking” dependence of corn growers on seedsman. “Cost of seed and the fact that a grower cannot save seed for future plantings has caused some growers to continue to grow open-pollinated corn.”

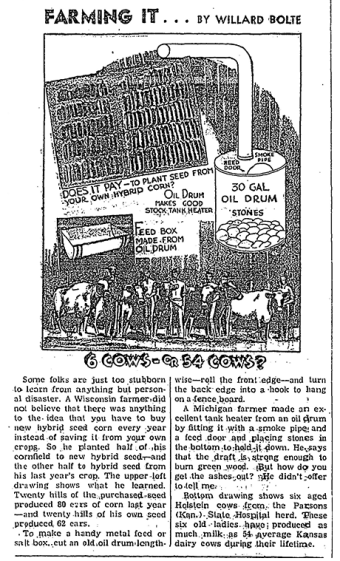

Some farmers did assume that they could save seed from a hybrid crop from the following year, and some tried planting it. The Suffolk County Farm News explained to its readers in 1933 that hybrid seed could not be saved and planted the following year, and noted the power this gave to seed sellers: “thus the seedsman who controls the parent pure lines controls the strain because the buyer is unable to propagate seed of his own…as is done with ordinary sweet corn.” In 1937, the Long Islander published a cautionary tale about saving seed in the form of a cartoon and an anecdote about a stubborn Wisconsin farmer who “did not believe that there was anything to the idea that you have to buy new hybrid seed every year instead of saving it from your own crops.” The drastically reduced yield from the re-used seed taught him a valuable — and expensive — lesson.

Farmers did not necessarily believe agricultural experts when they told them not to reuse hybrid seed. It was counterintuitive, since traditional plant breeding involved using the seed from the best plants, and hybrid corn plants were typically healthy and high-yielding. Many farmers probably suspected a swindle on the part of seedsmen and agricultural experts, and the only way to be sure was to see for yourself.

By the 1940s, corn growers and agricultural experts could look back over the past few decades and reflect on the dramatic changes that had taken place. In the spring of 1940, corn geneticist Ralph Singleton noted that only sixteen years had passed “since the first sweet corn hybrid was offered to the public.” This would have been in 1924, and the hybrid had been produced by Donald F. Jones, the inventor of the double-cross hybridization method. Singleton noted that “hybrid sweet corn…was grown only to a limited extent until 1932.” Here, he linked the history of hybrid corn with the economic crisis of the 1930s and the need to combat a serious outbreak of bacterial wilt: “The bottom year of the depression [1932] was also the year in which [the widely cultivated hybrid variety] Golden Cross Bantam was introduced…the rapid rise in the use of Golden Cross Bantam in the succeeding years more than equaled the rise of the stock market and business conditions from the depths to which they had sunk in 1932. At the time of its introduction there was a severe epidemic of bacterial wilt in the northeastern states. The ability of Golden Cross Bantam to produce a good yield of ears of excellent quality under severe environmental conditions not only created for itself a place in our permanent agriculture, but established hybrid sweet corn beyond any possible question.” Hybrid corn, in other words, had formed an important part of the recovery from the Great Depression, and this new technology had helped farmers weather the challenges thrown at them by nature.

During the 1940s, the older field-pollinated varieties of corn essentially vanished from cultivation. By 1942, there had been a decisive shift in New York State toward hybrid corn for sweet corn, grain and ensilage, due to “larger yields per acre, uniformity in size of ear and better quality of product,” as the East Hampton Star put it in December of 1942. The Suffolk County Farm Bureau News reported in 1944 that “the old fashioned open pollinated…varieties have almost disappeared from both Long Island and upstate farms.” In 1947, the Suffolk County Farm Bureau News announced that there was no room for the old varieties any more. “For any variety named, there is a hybrid that is better. That goes for yield, leafiness, standability and most any other factor you are interested in.”

Hybrids didn’t solve all the problems faced by corn growers, of course. Disease continued to be an issue. Many hybrids were resistant to corn wilt, but in 1961, the Suffolk County Farm Bureau News reported on a new fungal disease that had been attacking sweet corn in the New York region since the late 1950s — and there were no completely resistant hybrids. Biotechnology — which hybrid corn was, in its day — was not a panacea. Hybrids did not guarantee success for every commercial agricultural venture. In the late 1940s, farmers in Suffolk County discussed the possibility of producing hybrid seed corn themselves. The price of hybrid seed was high, which was good if you were producing it rather than buying it, and there was plenty of demand. They were aware of — and some of them probably remembered — the cooperative active in the late 1910s to produce and sell locally grown seed corn. “Suffolk County was formerly one of the leading seed corn producing areas, but it was discontinued for a variety of reasons…However since the development of hybrid corn, there appears no good reason why Long Island could not get back into the business,” the Suffolk County Farm Bureau News noted in 1948. In the end, this enterprise didn’t pan out because they could not find seed companies willing to contract with Long Island growers. All the companies they contacted preferred to stick with known contacts in the corn belt. A more modest plant to produce hybrid seed corn locally did work out, however, at least for a few years (see description of Philip Johnson’s business in the next section).

One of the most important things to understand about hybrid corn was that the effects of this new biotechnology were not limited to increased yields or the satisfaction of avoiding corn wilt. The fact that farmers had to buy their seed from seed dealers rather than producing it themselves by saving some of the previous year’s crop probably seemed like a relatively trivial change to people in the 1930s and 1940s. But the adoption of hybrid corn — and later, other hybrid crops — caused a series of seemingly small changes that added up over the decades to a revolution in American agriculture that no one in the 1920s or 1930s predicted. For example, hybrid corn had an effect on soil management and the need for fertilizers. Hybrid plants yielded more grain, but that grain didn’t come out of nowhere — the plant had to build it, using nutrients from the soil. Hybrid corn drew significantly more nitrogen from the soil than conventional varieties, and this meant that, as a local newspaper from Sayville explained in 1941, “a well-rounded program of soil management with the use of fertilizer is necessary if high production and soil fertility are to be maintained.” The amount of work it took to produce a bushel of corn fell during the middle of the twentieth century, in part due to the increased yields of hybrid varieties. This was good news for farmers, but not so much for the people providing farm labor — there simply weren’t as many jobs in agriculture as there had been in previous decades.

The scale and scope of the research that went into producing hybrid corn (and the other technologies, like modern fertilizers, that went with it) were enormous. People in the twentieth century sometimes referred to the ‘miracle’ of hybrid corn, but this technology didn’t fall fully formed from the sky. It took the work of a huge number of scientists at many universities and agricultural stations to make George Shull and Donald Jones’s insights into a marketable product. “It was the product of political machination, a solid decade of intensive research effort, and the application of human and financial resources” that were “enormous by any ordinary plant breeding standards,” as one plant breeder put it. The term ‘big science’ is often applied to the huge and complex technological and engineering projects of the Second World War and the Cold War. But it’s useful to ask whether it might not apply here as well, with hybrid corn being “agriculture’s Manhattan Project,” argues historian Jack Kloppenburg.

This might seem an exaggeration if you imagine only the rows of corn plants themselves, on the same farms as before, harvested by the same workers under the supervision of the same farmer. But technological changes seldom operate in isolation. Agricultural discoveries are designed to achieve specific goals when used as part of a specific management system. And “from the 1940s, the specified management system for which hybrid corn was being bred presupposed mechanization and the application of agrochemicals.” In other words, mechanical harvesting and fertilizers.

The development of hybrid corn and of mechanical harvesters went hand in hand. Traditional field-pollinated corn was not well suited to mechanical harvesting because “plants bore different numbers of ears at different places on the stalk. They ripened at different rates, and most varieties were susceptible to lodging (falling over).” But one of the things that made hybrid corn distinct from other varieties was its uniformity — ears ripened at the same time, at the same place on the stalk, which made it much easier for mechanical pickers to get all the grain without damaging any of it. Corn breeders began to design hybrid varieties that were intended to be machine-harvested, uniform in size, less likely to fall over, with “multiple ears and stiffer shanks connecting the ear to the stalk.” Once consequence of this design was that corn was harder to harvest by hand, which nudged farmers toward the use of mechanical pickers. Hybrid corn and mechanical harvesting equipment tended to go hand in hand — for farmers that could afford the investment.

A similar development took place with fertilizers. Beginning in the late 1950s, higher yields per plant and closer spacing (more plants per unit area of field) were accompanied by an explosion in the use of nitrogen fertilizer. Interestingly enough, it was an increase in the capacity to produce nitrogen during WWII that provided part of the impulse for this change — agricultural use seemed a good solution to the sudden excess of nitrogen, and agricultural scientists figured out how to breed hybrid corn that could tolerate, and use, large amounts of nitrogen. Between 1950 and 1980, nearly twice as much corn was sown on a given amount of acreage as before, “with the result that the volume of hybrid seed corn sales increased by 60 percent even though the number of acres in corn rose by only two percent…In that same span, the tonnage of nitrogen fertilizer applied to corn jumped by a factor of seventeen.” And this increased fertilizer use had other effects: “higher plant populations and more luxuriant growth provided ideal conditions for insect, disease and weed buildup, and this in turn encouraged the use of insecticides, fungicides and herbicides.” (The quotations above are from Jack Ralph Kloppenburg’s book on this subject, First the Seed.)

Discoveries don’t operate alone, in other words. Technological changes often come in packages — one invention or insight spurs on or necessitates others. The effects of these scientific and technological toolkits are often felt far beyond their immediate fields of application.

Photo Credits: (Luce’s favorite) Google Books. (Corn growing at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station) W. Ralph Singleton Collection, Box 5, Folder: Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous, 1934-1947, University of Virginia Small Special Collections Library. (Cartoon about hybrid corn) Historical Newspapers.