Scientific discoveries like hybrid corn had an enormous impact on the lives of everyone engaged in the business of agriculture on Long Island in the mid-twentieth century. But there were also more direct, personal ties between Long Island farmers and scientists working at institutions like Brookhaven or Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. What were these relationships like?

Scientists and farmers had skills and expertise in complementary areas, and often they could be of use to one another. For example, in 1948, when corn geneticist Ralph Singleton was preparing to leave his old position at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station and planning for his new job at Brookhaven National Laboratory, he found he needed some assistance. There was nowhere on site at Brookhaven where he could grow the corn he wanted to use for his experiments, so he and the chair of the lab’s biology department, Leslie Nims, decided to ask around to see if someone might be able to grow the corn for them. The Suffolk County Agricultural Agent, Walter Been, suggested to Singleton that he ought to write to Richard Gilmartin, the Suffolk County Commissioner of Welfare, whose office was just five miles away in Yaphank. The head farmer at the Suffolk County Home (a demonstration farm) might be able to grow Singleton’s corn. As it turned out, this farmer, Harry Hogan, was happy to do this. Gilmartin told Singleton that they would “be pleased to go over the farm with you and select any acre that might be best adapted to your needs. We would be pleased to prepare the land and keep it cultivated, free of weeds, etc., without charge and we would also be pleased to accept your offer for any sweet corn, hybrids and good productive ensilage types which might be adaptable to this climate.” Singleton thanked Gilmartin warmly. Singleton was happy to provide them with what they asked in return, explaining that “we have developed a number of rather good sweet corn hybrids and also some good productive ensilage types here at the Connecticut Experiment Station. If you would like seed of any of these we will be glad to supply it without charge.” Singleton needed Hogan and Gilmartin’s skills and expertise; Hogan and Gilmartin benefitted from the agricultural research that Singleton and others had done in Connecticut.

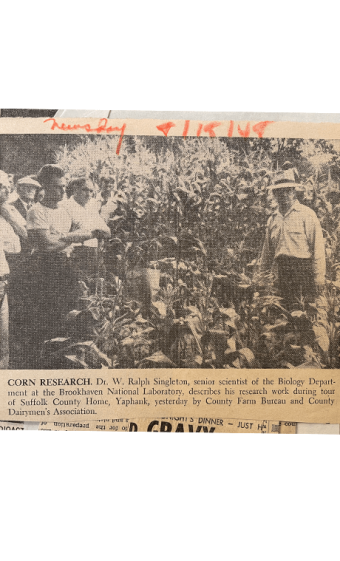

Singleton was also involved in a plan hatched in 1948 to grow and market hybrid seed corn in Suffolk County. Singleton and the Suffolk County Farm Bureau planned to collaborate in an effort to produce hybrid seed corn on Long Island and “sell the certified seed direct to other farmers in the northeast. Any corn not sold as seed could be sold to local poultrymen, duckmen and dairymen as feed. There would probably be no big profit in this but it might pay better than raising rye or wheat.” The Suffolk County Farm Bureau News emphasized Singleton’s expertise and his confidence in Long Island growers: “Dr. Ralph W. Singleton…is one of the foremost corn breeders in the United States, having developed many of the new sweet corn hybrids and sweet dent silage corns. He is willing to work with a few Suffolk County farmers and show them how to produce high quality hybrid seed corn. He states that foundation seed stock is available and that there is no reason why a few L. I. growers could not get into the business, if they wish to.” They also mentioned his cooperation with Gilmartin and Hogan, describing it as “a corn experiment at the County Farm in cooperation with Commissioner of Public Welfare Richard T. Gilmartin.” In the end, it turned out that the skills and expertise of Singleton and local farmers were not enough. The sticking point was seed merchants, who already had contacts in other areas of the country and had no compelling reason to change suppliers.

Farmers and scientists, though, saw themselves as being on the same team. Singleton remained interested in the project, and a little later, in 1950, a farmer named Philip Johnson in the town of Commack, working with Singleton, earned the distinction of being, according to the Suffolk County Farm Bureau News, “the first Long Island farmer to raise hybrid seed corn for grain and silage purposes.”

This type of collaboration was not limited to the plan to market locally produced and certified hybrid seed corn. Agricultural experts participated in local community events and offered advice on what varieties of corn and other agricultural plants to grow and developed varieties suited to local conditions — there was even a “Brookhaven” variety of corn, developed at the laboratory. Ralph Singleton wrote numerous articles about corn cultivation, varieties and diseases for the Suffolk County Farm Bureau News, and his children, Bill and Mary, packaged and sold seeds for home gardeners who wanted the best and newest varieties of hybrid sweet corn. In general, farmers welcomed the presence of research facilities like Brookhaven or Cornell’s agricultural research and extension center in Riverhead — decades later, looking back over the twentieth century, farmers thought that the specifics of Long Island’s agricultural challenges needed to be addressed by local research. What worked upstate or elsewhere in the country wouldn’t necessarily work in Suffolk County. Expertise was not a one way street, either. Singleton, for example, was described as being impressed with the extensive knowledge about hybrid corn that local hybrid seed authority Phil Johnson had developed in a relatively short time.

The relationship between Long Island scientists and farmers wasn’t all, or always, happy cooperation, however. One key area of potential conflict arose from the fact that scientists had many different types of connections and commitments — the institutions that they worked for and received funding from had broader scientific and political agendas that could come into conflict with what people living in the vicinity wanted. In the case of Brookhaven, for example, there were concerns about the potential effects of radiation from the facility’s reactors on people, animals and farms nearby. The Atomic Energy Commission, which supported a lot of research at Brookhaven, was interested for political reasons in promoting peaceful uses of atomic energy — the radiation biology experiments that were carried out there in the decades after World War II are a textbook example of this.

Part of the reason this research was so important was that in the 1940s and 1950s, the short- and long-term effects of radiation on living systems were not yet entirely clear. It was known that radiation at high doses was dangerous, of course — but it’s worth noting that even scientists were surprised that so many of the deaths resulting from the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki came not from the force of the explosions themselves, but from the radiation. When the Brookhaven laboratory was built on Long Island in the late 1940s, some people feared that there might be a threat from the radiation being created and used there. Given the state of knowledge at the time, their fears were not unrealistic.

Scientists and administrators at Brookhaven were aware of these concerns. They were also aware that there were some unknowns at play — even experts in nuclear science couldn’t say for sure what, if any, effects the facility might have on agriculture in the surrounding area. They were pretty sure that the effects would be essentially null. But there was always some uncertainty. In October of 1949, Brookhaven issued a report entitled Description of the Agricultural Industry in the Area Surrounding Brookhaven National Laboratory. The report noted that “operating of the nuclear reactor at Brookhaven Laboratory will result in some short lived radioactive gases being discharged into the atmosphere at the reactor site,” but asserted that this would not produce “enough [radiation] to affect to any appreciable extent plant and animal life in the area.” Nevertheless, the report emphasized the need to monitor surrounding agricultural output in order to be able to prove this. “Either with good intentions or bad, some people may claim some form of injury to their crops by the laboratory operations.” And if there happened to be positive effects on local agriculture, it was just as important to be able to document that as well.

The point that the report made about the need to be able to document positive as well as negative effects leads back to the larger political and scientific situation in which atomic research at Brookhaven was carried out. The reason they were doing experiments with radiation in the first place was that the effects of radiation exposure on living things were not understood in detail — some of the flagship experiments carried out at Brookhaven in the 1950s involved subjecting agricultural and other plants to varying doses of radiation in order to see what would happen. That there might be positive effects from the small amounts of radioactive gas released from Brookhaven was not out of the question. For several years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki a rumor circulated that the radiation had actually increased agricultural output in nearby agricultural areas — perhaps radiation could act as a kind of fertilizer? In the 1940s, radiation and nuclear technology probably still seemed like magic — a type of connection to the inner workings of nature itself that had enormous power.

Experiments to test whether radiation might actually act as a fertilizer were carried out by Ralph Singleton at the county farm in Yaphank — the same place where Gilmartin and Hogan had grown experimental corn for him. The Smithtown Beach Star reported on the work on “‘atomic’ fertilizers” and said that the research involved “growing corn from every stage of evolution, including the corn grass from which our present corn developed.” The experiment was probably a little more complicated than simply testing ‘atomic fertilizers,’ but those were the words that drew readers in.

Singleton wasn’t the only one to think that there might be some connection between radiation and increased yields. One theory put forth was that the radiation might have brought about “chromosome changes in plants.” That scientists theorized a connection between radiation-induced changes in plants and changes in chromosomes was entirely in step with genetic science in the decades after WWII — scientists in those years were very interested in karyotyping, or the imaging and analysis of chromosomes, because it was one of the few ways back then that the hereditary effects of things like radiation or pollution could be made visible. The idea was interesting enough that the Department of Agriculture tested it out in the late 1940s.

In the end, however, the connection between radioactive fallout in Japan and increased crop yields failed to pan out. The USDA came to the conclusion that there was “no beneficial effect upon either plant quality or growth.” By the late 1940s, soil specialists were arguing that there had indeed been an improvement in yield in the affected areas in Japan, but this was not due to radiation. Rather, it was because the ashes of wooden buildings incinerated by the blast added potash (which acts as fertilizer) to the soil. When Brookhaven scientists like Ralph Singleton talked to local people about the applications of nuclear technology in agriculture, they stressed ideas like how work with radioactive tracers, the sort of work that was being done at Brookhaven in the 1950s, helped scientists understand the basic processes at work inside plants and animals, or how they were exposing crop plants to limited, controlled amounts of radiation in order to induce potentially beneficial mutations that might result in disease resistance and higher yields. Such work was being done right next door: a scientist at the Long Island Vegetable Research Farm, for example, was using radioactive tracers in local potato fields to work out where potato plants were getting their phosphorus. All of this was a far cry from the drama and terror of the atomic bomb.

Nagasaki, Hiroshima, radioactive fallout and crop yields — this might seem very far away from advice from the local university or agricultural research station about the right variety of silage corn to plant on Long Island. But if the story of the connections between scientists and farmers on Long Island shows us anything, it’s that in the story of science and its applications to agriculture in the twentieth century, the local story and the bigger picture were always connected.

Photo Credits: (Singleton meets with Long Island farmers) W. Ralph Singleton Collection, Box 23, Folder: Newspaper Clippings and Journal, 1936-1954, University of Virginia Small Special Collections Library. (Suffolk County Extension Service Letterhead) W. Ralph Singleton Collection, Box 18, Folder: Speeches & Writings File, TMS “How Atomic Research Benefits the Farmer…January 20, 1954,” University of Virginia Small Special Collections Library.