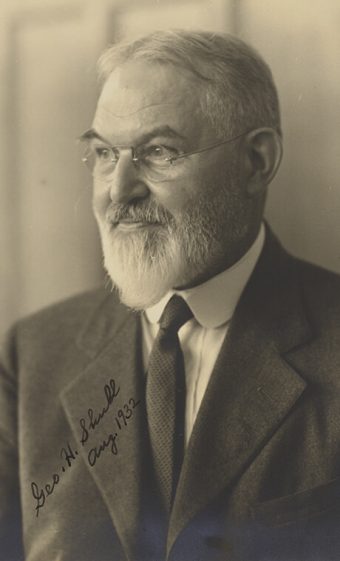

George Harrison Shull (1874-1954) was a plant geneticist and a former student of Charles Davenport, the director of the Carnegie Institution’s Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Shull was working at the Station for Experimental Evolution. Davenport had asked him to do two things. The first had to do with California plant breeder Luther Burbank — Davenport wanted Shull to find out the science behind Burbank’s skill at selecting and combining desirable traits in various fruits, vegetables and flowers. The second thing was to use corn (maize) to demonstrate the patterns of inheritance that Gregor Mendel had discovered in peas. Mendel had carried out his experiments in the 1850s and 1860s, publishing his results in 1866, but it was only in 1900 that his work was rediscovered by researchers interested in heredity. Shull, in other words, was pursuing a problem on the cutting edge of what would become the field of genetics: how specific traits were inherited, and how they could be inherited separately or combined together. Shull focused on two traits in corn that resulted from what we would describe as two alleles of the same gene. The dominant version of the gene produced full, starchy kernels and the recessive version produced wrinkled, sweet ones. Shull was able to establish a Mendelian inheritance pattern for this trait. In the course of this work, Shull saw that starchy ears and sugary ears had different numbers of rows of kernels. Was this trait also inherited according to the Mendelian pattern? This new research question led him to self-pollinate some of his experimental plants — that is, he inbred them. It was soon evident that inbreeding resulted in smaller, less healthy and less productive plants. But when Shull crossed two of these inbred plants, the result was counterintuitive: the hybrid offspring of two congenitally unhealthy parents was healthy and produced more seeds.

Photo Credit: W. Ralph Singleton papers, University of Virginia Special Collections.