Going from a scientific discovery to a commercial application is often trickier than it seems in retrospect. Shull saw the agricultural application of his discovery immediately, even though he himself didn’t plan to commercialize it. As he said in the 1909 paper in which he described how corn might be bred using his insight, this part of the process was “wholly outside my own field of experimentation.” He was also aware of one or two potential problems. The big one was that the seed for hybrid corn would be expensive to produce. To understand why, think through the process of producing the seed once more. There are two inbred lines of corn, neither which produces many seeds (corn kernels) due to the negative effects of the inbreeding. To produce the seeds that will be planted, and which will grow into the vigorous hybrid, plants from one inbred line are pollinated with pollen from another inbred line. This means that the plants that produce the seeds for the hybrids are themselves still of the sickly inbred variety — they don’t produce many seeds, even if we know that the seeds are different this time and are going to produce healthy plants when they in turn are planted. This was among the reasons that other experts, including the respected geneticist Edward M. East, were skeptical that this discovery could be applied successfully in agriculture.

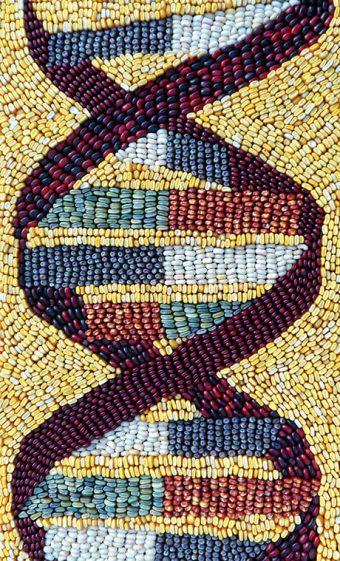

Photo Credit: Jason Wallace, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons