The story of the development of hybrid corn highlights an important point about the process of scientific discovery. We often imagine that discoveries are made by one person, at one institution, at a specific point in time. In reality, the process is often far messier and more interesting, with different people in different places contributing pieces of the puzzle. This is the case with hybrid corn. Shull was a geneticist, not an agricultural scientist — he didn’t see himself as the right person to go further with the practical application of his discovery, although he certainly hoped that agricultural scientists would do so. The person who did take the next step was Donald F. Jones, who worked at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven, Connecticut. Jones built upon Shull’s discovery in two ways. The first way was practical. As we saw earlier, the fact that the seed for the vigorous hybrid crop was produced by one of the inbred lines meant that not much of it was produced, since these lines were not healthy and did not produce a lot of seed; this meant that the seed for the hybrid crop was expensive. Jones found a way around this problem by using four inbred lines instead of two. Imagine four inbred lines, A, B, C, and D. Jones hybridized A with B and C with D. Then he crossed the AB hybrid with the CD hybrid. The resulting crop had the desired hybrid vigor, and the seeds for it were produced not by one of the inbred lines (A through D) but by one of the first-generation hybrids, AB or CD. This meant that the seed was more abundant and thus cheaper, making it cost-effective for farmers.

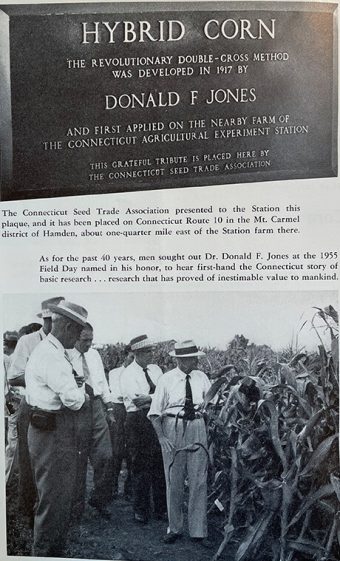

Photo Credit: W. Ralph Singleton papers, University of Virginia Special Collections.